Our perception of mental health is constantly evolving. Such is the case with three powerhouse mental health disorder classifications: anxiety, depression, and OCD. These three categories are currently among the most studied in the field of mental health. As more research is dedicated to the interactions between the three, treatments become more effective. Before understanding how OCD, anxiety, and depression interact, it is important to gain a firmer grasp on each individual definition.

The American Psychiatric Association defines depression (major depressive disorder, MDD) as a mood disorder that causes a substantial decrease in well-being, in regard to several different areas of life. On an emotional level, depression brings with it feelings of sadness, loneliness, emptiness, a lack of pleasure or energy, and hopelessness. On a cognitive level, depression engenders detrimental beliefs that negative experiences are the individual’s fault, that the world around them is a lonely and scary place, and that things will never improve. On an interpersonal level, depression is marked by actions and responses to others that destabilize their relationships and create a rift between the individual suffering from depression and those around them.

Depression can often severely hinder an individual’s sense of self-worth, their place in society, and their day-to-day functioning.

Depression Demographics: Depression is a relatively prevalent mental health disorder, affecting about one in 15 adults (or 6.7%) of the adult population. In the US, 17.3 million adults (7.1%) have reportedly experienced one or more depressive episodes during their lifetime.

Several risk factors have been shown to increase the chance of developing MDD. These include genetics, childhood environment, a temperamental inclination, later life events, and the existence of additional mental or medical conditions.

Major depressive disorder is part of the larger depressive disorders family, which includes dysthymia (persistent, less severe depressive disorder), premenstrual dysphoric disorder, substance/medication-induced depressive disorder, and depressive disorder due to another medical condition.

Anxiety is defined as an extreme, adverse and disproportionate concern over a possible threat. Unlike fear, which is seen as a measured response to a perceived threat, anxiety is characterized by its over-responsiveness to the potentially hazardous stimuli.

Anxiety Demographics: Anxiety is a family of disorders, with a large number of individuals facing them. In the US, 19.1% are diagnosed with at least one anxiety disorder, with 31.1% of US adults having dealt with an anxiety disorder sometime during their life.

Anxiety Demographics: Anxiety is a family of disorders, with a large number of individuals facing them. In the US, 19.1% are diagnosed with at least one anxiety disorder, with 31.1% of US adults having dealt with an anxiety disorder sometime during their life.

Anxiety and depression are both considered central mental health symptoms and are included in the definitions of many mental health disorders as defining attributes.

Both anxiety and depression have been associated with experiencing distress when facing the unknown, with depression related to a vague sense of mourning, and anxiety growing out of the thought of a future threat whose likelihood remains unclear. While depression is defined by a lack of energy, anxiety is perceived as more of a system overload, and tied to excessive concern over the possibility of coming to harm.

The anxiety family includes the following disorders:

Obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD, is a mental disorder defined as a combination of anxiety-inducing mental content and physical actions. OCD can be time-consuming, create significant amounts of distress, and impair functioning in several major life areas.

OCD in essence acts as an overactive defense mechanism that repeatedly introduces anxiety into the individual’s mental health system. It mainly consists of obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors that revolve around a common concern, such as cleanliness or personal safety, that has been kicked into hyperdrive.

Obsessive Thoughts: OCD-related thoughts tend to focus on one or more themes that cause the individual extreme distress. Such thoughts are intrusive, unwanted, and tend to repeat themselves in a ruminative fashion.

The four most common OCD-related themes are cleanliness and contamination concern, worry over catastrophic events, taboo thoughts, and “just right” thinking that overly focuses on symmetry and organization.

Compulsive Behavior: Individuals battling OCD often feel as if they are assailed by their own mind, due to their adverse, repetitive thought patterns. As a result, many develop rituals of repeated behavior in an effort to suppress their feeling of anxiety they experience. But while these behaviors can temporarily bring about relief, they eventually become compulsive, thus contributing to the individual’s rising levels of stress.

Examples of OCD-related behaviors are numerous, and include excessively scrubbing the floors, endlessly checking that all your home appliances are safely turned off, organizing and reorganizing your closets without end, or avoiding meeting someone in an attempt to prevent yourself from having negative thoughts about them.

OCD Demographics: 2.3% of US adults and 1%-2.3% of US children and adolescents face OCD. While this disorder can start at any age, OCD symptoms usually appear between the age of ten and early adulthood. It is worth noting that OCD can be hard to diagnose and is often explained away as personal idiosyncrasies. For this reason, it takes an average 14-17 years from the time symptoms become apparent until the patient begins receiving treatment.

OCD has been linked to a number of risk factors. These include genetics, environmental factors, temperament, and life events.

OCD is part of a range of what is referred to in the DSM-V as OCD-related disorders. The conditions in this group involve obsessive thought patterns and unwanted actions or ceremonies meant to alleviate feelings of anxiety. They include hoarding, trichotillomania (hair-pulling), excoriation (skin picking), hoarding, and body dysmorphic disorder (a preoccupation with a perceived physical defect).

All three of these conditions have something to do with the other two, though in somewhat different ways.

The connection between OCD and anxiety is the most straightforward, as anxiety is the central symptom to appear in OCD, and the reason why OCD was previously included within the anxiety family, instead of its own separate section in the two leading diagnostic manuals—the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-V and the World Health Organization’s ICD-10.

Listing OCD together with other anxiety-focused disorders made sense, since anxiety is OCD’s core symptom. However, several crucial developments in the field of OCD research have justified separating this disorder into its own category: first, cutting edge scientific discoveries have been able to map out the neural pathways and structures that play a part in the development of this condition; second, therapists in the field have noticed that specific treatments, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, are able to offer individuals with OCD some much-needed symptom relief; third, OCD-focused genetic research has uncovered genetic commonalities for OCD and OCD-related disorders, separating them further from other anxiety-based disorders.

As an anxiety-based condition, OCD and anxiety disorders stem from the same core symptom. But how do either anxiety or OCD relate to depression?

One rather intuitive link between both of these anxiety-centric categories and depression is based on causation: an individual who suffers from either OCD or anxiety may find themselves feeling hopeless, saddened or unable to enjoy life—all symptoms of depression. As such, facing either of these disorders for long can eventually cause them to develop depression as well.

Second, all three disorder families often appear together. As such, depression, anxiety, and OCD all show a high level of comorbidity with one another, with the probability of developing two or more of them together being significantly higher than chance. Unfortunately for those facing several of these conditions at once, comorbidity decreases the chances of a symptom-free recovery when compared to those battling singular disorders.

Genetics also seem to shape the relationship between these three conditions. The connection here seems to pass through neuroticism, a personality trait that causes intense, adverse reactions to internal and external stressors, resulting in feelings of sadness, guilt and anger. Since neuroticism has been found to be both highly hereditary and a risk factor for anxiety, depression, and OCD, researchers of this characteristic have hypothesized that it acts as a mediator between the three conditions.

Finally, neural structures also appear to play a part in the comorbid development of anxiety, OCD and depression. Specifically, the amygdala and its role in processing emotions has been shown to be associated with the development of these three disorders. This is particularly true when it comes to classical conditioning, which can attach a physiological or emotional response (such as sweating or sense of anxiety) to a certain stimulus (the appearance of a dog), after a bond is created linking the two to each other (a traumatic event such as being bitten by a dog). Indeed, damage to the amygdala has been shown to affect how we process and perceive threatening stimuli and expressions of happiness, which can result in the appearance of depression, anxiety and OCD-related symptoms.

Understanding which symptoms to focus your attention on is an important step in preparing a treatment course. To that end, there are several approaches to treating mental health comorbidities.

One common way is to assess which disorder is more central to the patient’s personality, or which one is presently causing them the greatest harm or distress: as mentioned earlier, depression can sometimes develop as a result of the hopelessness a patient might feel around their OCD. In such a case, treating their OCD could bring about a sense of relief and work to alleviate symptoms of their depression. For this reason, figuring which condition is causing the greatest disruption to an individual’s life can help focus their treatment on their more central source of suffering, while solidifying their belief that their situation can get better.

Another approach works according to a hierarchy of mental health disorders, stipulating that depression should be dealt with before treating any anxiety-based conditions. Proponents of this approach note that not only are all antidepressants also considered anxiolytics (anti-anxiety medication), but that the existence of depression in tandem with an anxiety-based disorder signals greater severity and a poorer prognosis. Taken together, these reasons build the case for depression being the more severe disorder, whose treatment could also alleviate symptoms of anxiety.

A third, somewhat subversive approach takes apart these three conditions, in an attempt to paint a broader picture of the patient’s life, beyond diagnostic mental health labels. Such a perspective is less concerned with whether a certain symptom, such as hyperarousal, is part of the patient’s OCD or anxiety, or whether their hopelessness is a sign of their OCD-based catastrophizing or due to a morose, depressive outlook on life. Instead, it tries to understand how each symptom fits into the individual’s overall experience, as part of their existing struggles.

Several major mental health treatments have been shown to offer significant relief from symptoms of OCD, anxiety, and depression.

Antidepressants: This mood-elevating group of medications, and particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), is considered a first-line treatment for anxiety, depression and OCD. This is due to SSRIs’ efficacy and safety in treating all three of these conditions, presumably by lowering the level of distress experienced by the individual battling them. SSRIs work by increasing the activation period of the neurotransmitter serotonin, which has been repeatedly shown to improve one’s sense of well-being, reduce the amygdala’s response to fearful stimuli, and decrease symptom severity in both anxiety and depression. In addition to SSRI medication, the antidepressant group serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) is considered a first-line treatment for depression and anxiety.

Psychodynamic Therapy: Psychodynamics have been found to be particularly effective with depression and certain anxiety-based disorders, though less so with OCD. This form of therapy offers an extended, deep-dive approach into the root causes the patient is facing, in an attempt to better understand the environment that facilitated their development. As the context in which they grew becomes clearer, the disorders they battle begin to appear less threatening, and more manageable.

CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and particularly exposure and response prevention (ERP), is also considered a first-line treatment for OCD, due to its proven efficacy in treating this condition. CBT works by systematically identifying detrimental beliefs, exhausting obsessions and distressing, compulsive behavior, in an attempt to establish a firmer sense of control when faced with destabilizing stimuli.

Deep TMS: Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, or Deep TMS, is an advancement of the traditional, figure-8 TMS that came before it, which manages to address some of the issues raised by its predecessor.

A non-invasive treatment, Deep TMS utilizes a magnetic field to safely and effectively regulate the neural activity of brain structures found to be related to a number of mental health conditions. This treatment does not require anesthesia and can be incorporated into an individual’s daily routine.

Deep TMS manages to overcome the range and targeting limitation that traditional TMS faces, thanks to Deep TMS’s patented H-Coil technology, which is held inside a cushioned helmet fitted to the patient’s head. The H-Coil produces magnetic fields that are able to directly reach wider and deeper areas of the brain, thereby increasing the treatment’s efficacy and safety.

Deep TMS manages to overcome the range and targeting limitation that traditional TMS faces, thanks to Deep TMS’s patented H-Coil technology, which is held inside a cushioned helmet fitted to the patient’s head. The H-Coil produces magnetic fields that are able to directly reach wider and deeper areas of the brain, thereby increasing the treatment’s efficacy and safety.

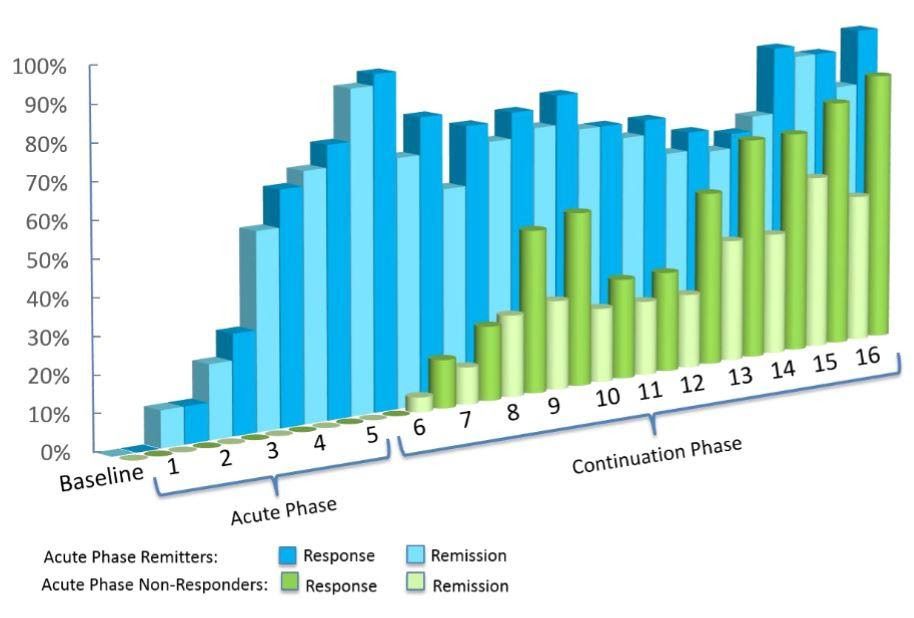

Deep TMS’s efficacy was confirmed in a 2015 multicenter, sham-controlled study published in World Psychiatry. The study concluded that one out of three patients with treatment-resistant MDD managed to achieve remission after undergoing four weeks of Deep TMS treatment’s acute phase.

Furthermore, close to 80% of the remaining patients went on to experience an improvement during the continuation phase.

Deep TMS was recorded to have even higher efficacy rates in a real-life setting. From the data of over 1000 participants receiving Deep TMS for MDD, roughly 75% achieved a clinical response, with one out of two patients reaching remission.

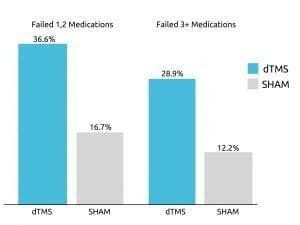

The treatment’s efficacy for OCD was also further substantiated in a 2019 multicenter, sham-controlled study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry. The study specifically found that regulating the functions of “the medial prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex significantly improved OCD symptoms.”

In addition to its effectiveness as a standalone treatment, Deep TMS can also be combined with all kinds of medication or additional therapies. A 2019 study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research highlighted its ability to integrate into a broader treatment course, finding that it achieved significantly higher remission rates when combined with medication treatment, as opposed to medication alone.

Deep TMS has also been shown to offer a safe treatment process, without any long-lasting, substantial or systemic side effects. A 2007 study published by Clinical Neurophysiology confirmed this, stating that Deep TMS is a well-tolerated form of therapy that does not cause adverse physical or neurological side effects.

It is this combination of effectiveness and safety that in 2013 granted Deep TMS its FDA clearance status for depression. Deep TMS is also the first non-invasive medical device to be given FDA clearance status for treating OCD. Most recently, in 2020 it was awarded an FDA-clearance status as a treatment for smoking cessation. Deep TMS is also CE-marked in Europe, as a treatment option for these and a number of other mental health conditions

While effective as standalone treatments, it should also be mentioned that combining different forms of treatments can have a greater effect than each treatment on its own. This has been shown to be the case in both anxiety and depression-based treatments, specifically when combining SSRI medication with a cognitive-focused form of psychotherapy, such as CBT, or combining medication treatment with Deep TMS.